Dying to be Alive (Part 1): Why it’s so Hard to Live Your Unlived Live and how You Actually Can

“I wish I’d had the courage to live life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

This is the number 1 regret of dying people according to bestselling author and former palliative care nurse Bronnie Ware.

When I talk about the unlived life, that’s exactly what I’m talking about: a life that is authentic to who you are and what you stand for, not what others expect you to be and stand for. A life you won’t regret on your deathbed, leaving a legacy you’re proud of. And a life that you - for whatever reason – haven’t turned into your actual, lived life yet.

Why it’s so hard to live true to ourselves is something that has always puzzled me.

Sure, there are social influences like our families’ and society’s expectations about how we should live our lives. These are important, of course, and at some point I might write about them, too.

But I believe there is a much more fundamental reason why we so often fail to live our lives true to ourselves.

So that’s the question I’m going to address today.

Why is it so hard to live true to ourselves?

On the surface, things look pretty straightforward:

We all know we will die one day – that’s a fact. Therefore, our time is limited. So we should spend what little time we have on the things that matter most to us.

Sounds logical, right?

Yet, that’s not how most people act.

Instead, almost everybody acts as if they were immortal.

We think we aren’t ready yet.

Or there’s something more urgent.

Or we think the conditions just aren’t right yet.

We think it’s fine to work for a few years at a job we don’t give a shit about just for the money because we still have time to change that sometime in the future.

We think it’s fine to compromise on how we live our lives because others expect that from us. Because we think we still have time to change that sometime in the future and start living a life true to ourselves.

We keep pushing back the things that matter to us to some indeterminate future.

We act as if there will always be more time in the future for us to do what we really want to do.

One way or another, we always believe we still have time.

All the while, one grain of sand after the other trickles through the hourglass of our lives.

Until there are no more grains left, and it’s too late for us to change anything.

As a result, many people die full of regrets for having lived a life that ultimately wasn’t theirs. Or they die before they get around to living the unlived life they wanted.

Why do humans act like this?

The Denial of Death

The best answer I found so far comes from a book called ‘The Denial of Death’ by Ernest Becker, and from a research field called ‘terror management’ which was sparked by Becker’s work.

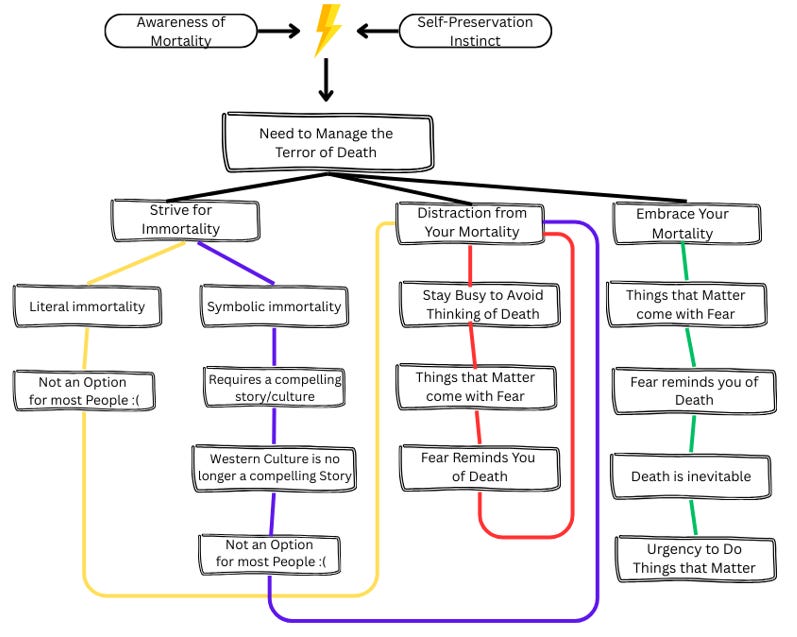

The argument that follows is a bit complicated, so I made you a (highly professional 😉) flowchart that shows it at a glance. Whenever you get lost, scroll back to this chart.

Let’s begin:

Becker states that humans are the only species who are aware of their mortality.

This awareness conflicts with our self-preservation instinct, which is a fundamental biological instinct. The idea that one day we will just not exist anymore fills us with terror – a terror that we have to manage somehow, lest we run around like headless chickens all day (hence ‘terror management’).

How do we manage that terror of death?

We do it in one of two ways:

Striving for literal or symbolic immortality

Suppressing our awareness of our mortality

Let’s look at striving for immortality first.

Striving for immortality

There are two ways to become immortal – literally or symbolically.

Literal immortality

This is what religions promise:

When you die, your soul will survive and go on living in paradise.

The drive for literal immortality is also behind many transhumanist projects like mind uploading or biological immortality. In this sense, they are surrogate religions.

The problem with literal immortality is that nobody can be sure whether they will actually go on living after their physical death (in whatever shape or form).

And those transhumanist projects I mentioned haven’t yet reached their goal of achieving literal immortality, either (and if they ever get there, I’m pretty sure their feelings of triumph will be short-lived. But that’s a topic for another essay).

So if you’re a believer in a religion and you believe that you will literally become immortal – you’re good.

But most people, even many believers, don’t have enough conviction in that.

Instead, they look to…

Symbolic immortality

Symbolic immortality means that a meaningful part of us survives when we die.

Culture is built around ways to achieve this kind of immortality:

Have kids that survive us

Build a business that keeps existing when we’re gone

Invent something that changes how people live forever

Build an empire and write our name into the history books

Create a great piece of art that people admire long after we’re gone

Create a theory or idea that changes how we see the world or ourselves

Through symbolic immortality, we make ourselves part of a bigger story. One that started long before us and will continue long after we’re gone – namely, our culture and society.

By becoming a significant part of that larger story, in a symbolic way, we become immortal.

So when we manage our terror of death by trying to become symbolically immortal, we do things that are valued in the culture and society we’re part of.

As long as what we value personally and what is valued in our society are congruent, we feel like we’re doing something meaningful. And because what we’re doing is meaningful, the risk of dying full of regrets is low.

The problem with symbolic immortality is that it’s only possible if our culture actually has values that mean anything and that aren’t completely empty. The story of our culture needs to resonate with us for us to want to be a part of it.

If “anything goes” and “make as much money as you can” are the only values there are, there is no substance to the culture because these values don’t point to anything that transcends our individual lives. They are just as small as we are. It just isn’t a story that is compelling enough for most people to want to play a part in – and (symbolically) die for.

Sadly, this is the state Western culture is currently in.

As Becker puts it:

„[Man] has to feel and believe that what he is doing is truly heroic, timeless, and supremely meaningful. The crisis of modern society is precisely that the youth no longer feel heroic in the plan for action that their culture has set up. […] We are living a crisis of heroism.“

I wrote about the reason why we no longer live in a compelling culture/story before, so I won’t repeat my argument here.

In short, the fundamental reason is that the analytical, mechanistic, detached look at the world has become dominant in our culture, as Iain McGilchrist argues at length in The Master and His Emissary.

It’s a way of looking at the world that isolates and atomizes everything it turns to – including us, and the culture and society we live in.

One of the main results of this development is that we have become uprooted and disconnected from everything that once gave our lives meaning – social connections, the stories that once made up our culture, our history, the surroundings we grew up in, and so on.

There is no compelling story we’re part of anymore.

Actually, it’s even worse, because it no longer seems natural to us that there should be something bigger than us and our individual lives. Iain McGilchrist talks about that in this video:

As I have argued in my article, we treat ourselves as machines. Machines don’t have a higher purpose. They merely serve a function, and they are replaceable.

So not only is there no bigger, compelling story anymore that we could be a part of, but we also don’t believe anymore that we have a unique role to play in that story even if it were still there.

All in all, that means, just like literal immortality, symbolic immortality is no longer an effective way to manage our terror of death for many people - and no longer the path to a life we won’t regret.

That leaves us only the second option of managing the terror of death:

Suppressing our awareness of our mortality

What do you do when you must find a way to become immortal, but there just isn’t a way to do so?

One thing you can do is deny that you’re mortal and act as if you already are immortal - as if you will always have more time.

Which is exactly how most people act!

Instead of spending our time on the things that matter, we distract ourselves with stuff that keeps our minds busy and away from thinking about the fact that we’ll die one day.

Things like

That job that ultimately doesn’t matter

Striving to be ‘productive’ at all times

Mindless entertainment

Staying busy

Gossip

Parties

Anything to keep us distracted from our mortality.

Why do we act like that?

Because:

There is no compelling story we’re part of and that would tell us what matters and what doesn’t, and

when you say that something matters and something else doesn’t, you acknowledge that you are finite – that you can’t do it all.

And that would imply you aren’t immortal and you don’t have unlimited time.

Merely by calling them “things that matter to me”, they remind us of our mortality because things matter only when there are limits – when we can’t do it all. Only then can one thing have a higher priority than another.

And so we feel no urgency to get to the things that really matter.

Because the only way to create that urgency is to face the fact that you will die.

And if you constantly distract yourself from that fact, you can’t feel that urgency.

I believe both things taken together – the lack of a compelling, overarching story we can be a part of to become immortal, and us distracting ourselves from our mortality (which is a result of the lack of an overarching compelling story), are the fundamental reason why it’s so hard to live our unlived lives.

Because ultimately, by distracting ourselves from our mortality, we also distract ourselves from the things that matter to us.

If you say something matters to you, what, you’re saying is that you’re emotionally invested in it.

That means you caring about whether those things that matter to you will be a success or not.

If you care about starting a business, you care about whether you succeed or not at that.

If you care about being the best parent you can be, you care about whether you succeed or not at that.

If you care about getting to know that attractive stranger, you care about whether you’ll succeed at that.

And that emotional investment causes fear and discomfort.

Why? Because in any valuable endeavor, success is never guaranteed.

There is always a risk of failure. And that uncertainty about whether you’ll succeed or not causes anxiety.

And the more you care about something, the more fear you’ll feel.

Here’s where things get interesting:

What is the source of those fears?

Ultimately, all fears can be traced back to our old friend - the fear of death.

Think of some of the most common fears:

Fear of public speaking —> Fear of ridicule and social ostracization —> fear of death

Fear of spiders —> fear of poisoning —> fear of death

Fear of talking to strangers —> fear of rejection —> fear of social ostracization —> fear of death

Fear of promoting yourself or your business —> fear of rejection —> fear of social ostracization —> fear of death

Now, if promoting your business matters to you, and you feel fear because you care so much about the outcome - guess what happens when you live in denial of your mortality, like most people do?

You will have a much harder time getting over your fear of promoting your business because it triggers that basic fear of death you spend so much energy avoiding!

Instead, you’ll keep distracting yourself from facing your fear of promotion because it’s connected to your fear of death, and that fear must be avoided at all costs, as we have seen.

That means you’ll

procrastinate

overprepare

overanalyze

overcomplicate

strive for perfection

‘clear the decks’ before you can get to this thing that matters, because you’re telling yourself it will require your full focus. All the while the faster you’re clearing the decks, the faster they fill up again.

All of these are avoidance techniques. And ultimately, what you’re avoiding is your fear of death.

Let’s summarize what we talked about so far:

Distracting themselves from their mortality is the default way for managing their fear of death for most people.

Living your unlived life means doing things that matter to you.

The things that matter to you always trigger fear.

Each one of those fears can be traced back to the fear of death.

That leads us to the paradox of living your unlived life:

The more you avoid facing death, the farther you’re running away from your unlived life.

Put more drastically: The more you avoid facing death, the more certain it becomes you’ll die with regrets.

And vice versa, the more you embrace your mortality, the more courageous you’ll be, and the less likely you’ll die with regrets.

How to Live Your Unlived Life

So what it all comes down to is this:

To live a life we won’t regret, we need to stop distracting us from our mortality and look it right in the eye.

The stoics knew this: Memento mori – remember that you’re mortal – was one of their mantras for a good life.

Which sounds easy on paper, but is fucking hard to do in practice.

And it’s only one half of the equation…

The other half is actually doing the stuff we care about – the things that make up our unlived life.

In part 2 of this series, I’ll talk about how to do both these things – face the fear of death and do the stuff that matters to you.